There has been a great deal written about the ill-fated May 17, 1943 Ijmuiden Mission which was named after the target that day, a power plant in Holland. None of the 11 B-26 Marauders from the 450th and 452nd Squadrons of the 322nd Bomber Group returned that day.

More on this later but it is important to note that this mission was an exact repeat of the very first mission in Europe by the 322nd flown three days earlier on May 14th. Reconnaissance photos had apparently shown that the bombs from the Marauders had missed their target on that date, though there is still dispute to this day on this point. Unbeknown to Jim Hoel who was to fly in his first Mission on May 17, the 322nd Group Commander, Colonel Robert M. "Moose" Stillman, who had led the misson on the 14th, argued vehemently with higher command that repeating the mission three days later with the Germans now precisely prepared, was a suicide mission. His pleas were denied but despite this, Stillman still insisted on leading the May 17th Mission.

Robert F. Freeman, in his book,

B-26 Marauder At War, quoted this exchange just before the 450th and 452nd Squadrons of Marauders were to take off on May 17th:

"For Stillman, convinced the mission was sheer folly, yet determined in his duty to personally see the target hit this time, it was a dispirited departure from the intelligence section. Von Kolnitz said "Cheerio" as Stillman was leaving. 'No, it's good-bye', the commander responded. Ignoring the prophesy Von Kolnitz said, 'I'll see you at one-o'clock.' 'It's good-bye' repeated Stillman and walked out."Jim knew none of this when his plane went down on May 17th though there were general feelings of gloom amongst the airmen that morning sensing they would meet stiffer resistance.

Jim's B-26 hadn't been over the coast long (maybe only a few minutes) when it became apparent that there was some kind of trouble. When the pilot called for him to "Go back and see what's the matter with the radio operator," Jim was sitting in the nose of the airplane. When Jim got to the radio operator, he didn't know whether he had been hit by flack though it didn't appear so. He might have been jostled some way or other, but he was sort of wide-eyed, and standing up in the radio navigating compartment. Jim sat him down in his radio seat and strapped him in, and about that time, the pilot said, "Standby, I think we're going to ditch (meaning in the water)."

With that, Jim reached up and opened the hatch on top of the airplane and the radio compartment and then sat down with his back to the bulkhead between the pilots' compartment and where he was sitting in the radio navigating compartment. The training that Jim and the others had gone through taught the tail gunner and the turret gunner, when they heard on their earphones that that they were going to crash or prepare for an emergency landing, they were to come walking through the 2 bomb bay doors and each of them sit, one between Jim's legs and the other between the radio operator's, all with their backs to the front of the airplane so that they could take the blow of the crash as they hit.

But the gunners never came through. Jim felt that they had plenty of time to do it. He's always thought that. But they never showed up. And about that time, the airplane hit the water.

Another rule in landing was, when you hit the water in a crash landing, don't ever stand upright because chances are that there will be a "skip" that you will hit the water and skip a little bit and then you are going to hit the water with the second blow which is going to be devastating and the final stop of the airplane.

Jim didn't stand up for the simple reason that he was sitting, waiting for the second blow. It seemed like an hour-it might have been a few seconds. At any rate, there wasn't a second. When the Marauder hit the water, it was nosed right and stopped immediately. As a result, Jim was immediately almost over his head sitting in water, but as he started to get up, he couldn't. There was something that seemed to be in front of him and he ran his hands around whatever it was. it was a 500-pound bomb that had come through the bulkhead and was sitting there on something, but it was not sitting on Jim's legs. It was just in front of him, and luckily he was able to slide out from under it.

By now, Jim was up to his neck in water standing up, while the radio operator, was standing in the hatchway going out. He was hollering something about his foot being caught. Jim knew that if he didn't get out, Jim wasn't either, so he wrapped his arms around his legs and gave the radio operator a tremendous boost up and that loosened his foot from whatever it was caught in. The radio operator went sailing out and Jim was immediately behind him.

Jim's May West (the emergency vest worn on your chest) had 2 compartments to it--one on each side and each one of them had a carbon dioxide bottle. For some reason or other, one of Jim's compartments was inoperable. It probably had small flack holes in it and when he pulled the tubes, it wouldn't hold air so there he was. Jim had gotten his heavy chest protector off, but he couldn't get the leg ones off, and he was about to sink. Just then the radio operator started wrapping his arms around Jim and he realized that he hadn't pulled

his Mae West, so Jim reached down and pulled both the carbon dioxide bottles on the operator's vest and that was enough to sustain and hold both of them afloat.

They were in this huge, wide, straight canal and it seemed clear that the squadron had missed its planned landfall considerably. They had no idea what this was or where they were. In later years Jim learned that it was known as the "Nieuwe Waterweg River". It is a wide, wide shipping canal that runs adjacent to the Rhine River into the North Sea.

By this time it appeared the Marauder had completely disappeared. Here they were, the two of them floating, but as they looked around they saw the tail section of the airplane floating right straight up (standing straight up in the air) and what evidently had happened was that when the plane hit the water, the force was so great that it broke the airplane in two parts. Jim guessed that the first half was from the turret gunner's area forward, and that the front part of the airplane hit the water and just kept going down. The tail section without that much of the fuselage stood up and in doing so was sort of floating because it had air in it. But it was sinking fast and they could only watch it go down.

The two of them thought they were the only two alive when suddenly with a bang on their bottoms the copilot popped up. He was choking a little bit because he had been under water for quite some time. But he seemed all right and said "I'm fine." Then a couple of seconds later, the pilot of the airplane burst to the surface and he was just absolutely choking to death. They all looked at him and they said, "My God, you've been under water so long, come over here, let's help you some way or other." They then noticed that the steel helmet that he had on, when we hit in the crash, was pushed way back on his head so the strap under his chin was choking him. The other three reached up and undid the strap and with that he was still coughing a lot, but he was okay. Four of the six crewman were alive floating in the Nieuwe Waterweg River.

The four survivors started swimming slowly to the shore on their right.

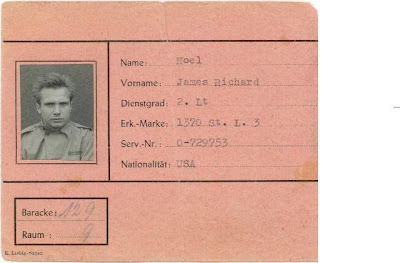

Jim Hoel, our father, was transported and processed into Stalug Luft III about 10 days after his capture, on May 17,1943. Though he was able to write home, apparently the brief posts he sent were not received until months later.

Jim Hoel, our father, was transported and processed into Stalug Luft III about 10 days after his capture, on May 17,1943. Though he was able to write home, apparently the brief posts he sent were not received until months later.

In the previous post, the importance of Jim

In the previous post, the importance of Jim

A number of years ago, on a Veteran’s Day, my father, was asked to talk to our church in Chicago about his experiences during World War II. I sat with my family in the front row amidst a number of other veterans and their families, most in their 70’s and 80’s. In front of us on the floor sat the congregation’s youngest members, children ranging in ages from 4 to 10.

A number of years ago, on a Veteran’s Day, my father, was asked to talk to our church in Chicago about his experiences during World War II. I sat with my family in the front row amidst a number of other veterans and their families, most in their 70’s and 80’s. In front of us on the floor sat the congregation’s youngest members, children ranging in ages from 4 to 10.